System Failure: 7 Shocking Causes and How to Prevent Them

System failure isn’t just a technical glitch—it’s a domino effect waiting to happen. From power grids to software networks, when systems collapse, chaos follows. Let’s uncover what really goes wrong and how we can stop it.

Understanding System Failure: The Core Concept

At its essence, a system failure occurs when a structured network—be it mechanical, digital, or organizational—ceases to perform its intended function. This breakdown can be sudden or gradual, localized or widespread, but its impact is almost always disruptive. Whether it’s a server crash during peak traffic or a bridge collapsing under structural strain, the root lies in interconnected components failing to operate in harmony.

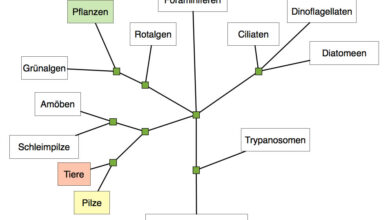

What Defines a System?

A system is any set of interrelated parts working together toward a common goal. This could be as simple as a home thermostat regulating temperature or as complex as a global financial trading platform. Systems are designed with inputs, processes, outputs, and feedback loops to maintain stability and efficiency.

- Inputs: Data, energy, or materials that enter the system

- Processes: The mechanisms that transform inputs into outputs

- Outputs: The results produced by the system

- Feedback: Information used to adjust performance and maintain balance

When any of these elements fail or become misaligned, the entire system is at risk.

Types of System Failures

Not all system failures are created equal. They vary based on origin, scope, and impact. Some common classifications include:

- Hardware Failure: Physical components like servers, sensors, or engines malfunctioning.

- Software Failure: Bugs, crashes, or security breaches in code.

- Human Error: Mistakes in operation, configuration, or decision-making.

- Environmental Failure: External factors like natural disasters or power outages.

- Design Flaw: Inherent weaknesses in the system’s architecture.

Understanding these types helps in diagnosing and preventing future incidents.

“A system is never stronger than its weakest link.” — Often attributed to engineering principles, this quote underscores the vulnerability of interconnected systems.

Common Causes of System Failure

Behind every system failure lies a chain of causes—some obvious, others hidden. Identifying these is the first step toward building resilience. While no system is immune, recognizing patterns can significantly reduce risk.

Design and Engineering Flaws

One of the most insidious causes of system failure is poor initial design. When engineers overlook stress points, fail to account for edge cases, or prioritize cost over safety, the foundation is compromised from the start.

For example, the collapse of the World Trade Center towers in 2001 was not solely due to the plane impacts but also due to design vulnerabilities in fireproofing and structural redundancy. Similarly, the Therac-25 radiation therapy machine caused fatal overdoses in the 1980s due to a software race condition that was never tested under real-world conditions.

- Lack of redundancy in critical components

- Inadequate stress testing during development

- Over-reliance on single points of failure

These flaws often remain dormant until triggered by an external event, making them especially dangerous.

Software Bugs and Glitches

In our digital age, software underpins nearly every system—from banking to aviation. Yet, even a single line of faulty code can trigger catastrophic failure.

The 1996 failure of the Ariane 5 rocket, which exploded 37 seconds after launch, was caused by a software error involving a 64-bit floating-point number being converted to a 16-bit integer. The code, reused from Ariane 4, wasn’t designed for the higher velocity of the new rocket. This single oversight cost over $370 million.

- Uncaught exceptions and memory leaks

- Poor error handling and logging

- Inadequate version control and testing protocols

As systems grow more complex, the surface area for bugs expands exponentially. Rigorous testing, code reviews, and automated monitoring are essential defenses.

Human Error and Organizational Breakdown

Despite advances in automation, humans remain central to system operation—and often the weakest link. Human error contributes to over 70% of industrial accidents, according to the UK Health and Safety Executive.

Miscommunication and Training Gaps

One of the most common human-related causes of system failure is miscommunication. In high-stakes environments like hospitals or nuclear plants, unclear instructions or jargon can lead to fatal mistakes.

The 1979 Three Mile Island nuclear accident was largely attributed to operators misreading a valve status due to poor interface design and inadequate training. The valve was stuck open, but the control panel indicated it was closed, leading to a partial meltdown.

- Lack of standardized communication protocols

- Inadequate training for emergency scenarios

- Overload of information leading to cognitive fatigue

Organizations must invest in clear procedures, simulation training, and human-centered design to mitigate these risks.

Complacency and Overconfidence

When systems run smoothly for long periods, a culture of complacency can develop. Operators may skip safety checks, ignore warning signs, or assume backups will always work.

The 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill was preceded by multiple ignored warnings and bypassed safety systems. Engineers had disabled alarms and overridden automated shutdowns to meet deadlines, assuming the well was stable. The result was the largest marine oil spill in history.

“It can’t happen here” is the most dangerous phrase in risk management.

Regular audits, anonymous reporting systems, and a strong safety culture are vital to counteract overconfidence.

Environmental and External Triggers

Even the most robust systems can fall victim to forces beyond human control. Natural disasters, cyberattacks, and supply chain disruptions are external triggers that can initiate or accelerate system failure.

Natural Disasters and Climate Events

Earthquakes, floods, hurricanes, and wildfires can disable infrastructure in seconds. In 2011, the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami in Japan triggered a chain reaction that led to the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster.

The plant’s backup generators, located in basements, were flooded and failed, leading to a loss of cooling and subsequent meltdowns. This was a classic case of a system failure caused by underestimating environmental risk.

- Inadequate site selection for critical infrastructure

- Lack of waterproofing or seismic reinforcement

- Failure to plan for cascading failures

Modern risk assessments must incorporate climate change projections and extreme event modeling.

Cyberattacks and Digital Sabotage

In the digital era, system failure is increasingly caused by malicious actors. Cyberattacks can disable power grids, steal data, or manipulate industrial controls.

The 2015 cyberattack on Ukraine’s power grid, attributed to Russian hackers, left over 230,000 people without electricity. The attackers used spear-phishing emails to gain access, then deployed malware to disable circuit breakers remotely.

- Outdated software with unpatched vulnerabilities

- Insufficient network segmentation

- Lack of real-time intrusion detection

According to CISA (Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency), critical infrastructure sectors are under constant threat. Proactive defense, employee training, and zero-trust architectures are essential.

Case Studies of Major System Failures

History is littered with system failures that offer painful but valuable lessons. By studying these, we can identify patterns and prevent repetition.

The Challenger Space Shuttle Disaster (1986)

The explosion of the Space Shuttle Challenger 73 seconds after launch killed all seven crew members. The immediate cause was the failure of an O-ring seal in one of the solid rocket boosters, which had become brittle in cold weather.

However, the deeper cause was organizational: NASA managers ignored warnings from engineers about launching in below-freezing temperatures. Pressure to maintain schedule overrode safety concerns.

- Failure to heed technical warnings

- Breakdown in decision-making hierarchy

- Normalization of deviance (accepting small risks as routine)

This tragedy reshaped NASA’s safety culture and led to major reforms in risk assessment.

The 2003 Northeast Blackout

One of the largest power outages in North American history affected 55 million people across the U.S. and Canada. It began with a software bug in an Ohio energy company’s alarm system, which failed to alert operators to overgrown trees touching power lines.

As voltage dropped, the system couldn’t reroute power, leading to a cascading failure. Within minutes, the entire grid collapsed.

- Inadequate monitoring systems

- Lack of coordination between regional operators

- Failure to maintain transmission corridors

The event led to the creation of mandatory reliability standards enforced by the North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC).

Preventing System Failure: Best Practices

While no system can be 100% failure-proof, robust strategies can dramatically reduce risk. Prevention requires a combination of technology, culture, and continuous improvement.

Redundancy and Fail-Safe Design

Redundancy means building backup systems that can take over if the primary one fails. This is common in aviation, where multiple flight control systems operate in parallel.

Fail-safe design ensures that when a failure occurs, the system defaults to a safe state. For example, elevators have brakes that engage automatically if the cable breaks.

- Duplicate critical components (e.g., power supplies, servers)

- Use diverse technologies to avoid common-mode failures

- Implement automatic shutdown or isolation mechanisms

The aviation industry’s “triple modular redundancy” is a gold standard—three independent systems vote on the correct action, minimizing error.

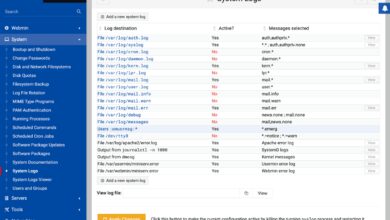

Regular Maintenance and Monitoring

Preventive maintenance is crucial. Equipment degrades over time, and without inspection, small issues become catastrophic failures.

Bridges, for instance, require regular stress testing and corrosion checks. The 2007 collapse of the I-35W Mississippi River bridge in Minneapolis was linked to undersized gusset plates that had been stressed for decades.

- Schedule routine inspections and component replacements

- Use sensors and IoT devices for real-time monitoring

- Keep detailed logs for predictive analytics

Modern predictive maintenance uses AI to analyze data trends and forecast failures before they happen.

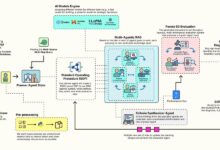

The Role of AI and Automation in System Resilience

Artificial intelligence is transforming how we detect, respond to, and prevent system failure. From self-healing networks to predictive analytics, AI offers powerful tools for enhancing reliability.

AI-Powered Predictive Analytics

Machine learning models can analyze vast amounts of operational data to identify patterns that precede failure. For example, AI can detect subtle vibrations in a turbine that indicate impending mechanical breakdown.

General Electric uses AI to monitor jet engines in real time, predicting maintenance needs and reducing unplanned downtime by up to 30%.

- Train models on historical failure data

- Integrate real-time sensor feeds

- Generate early warning alerts for human operators

However, AI is only as good as its data. Biased or incomplete datasets can lead to false predictions.

Self-Healing Systems and Autonomous Recovery

Next-generation systems are being designed to detect and fix problems without human intervention. These “self-healing” systems use automation to reconfigure, restart, or isolate faulty components.

In cloud computing, platforms like AWS and Azure automatically reroute traffic when a server fails. Similarly, smart grids can isolate damaged sections and restore power to unaffected areas.

- Automated failover to backup systems

- Dynamic resource allocation based on load

- Autonomous patching and updates

The goal is not to eliminate human oversight but to reduce response time and minimize damage.

System Failure in Different Industries

While the principles of system failure are universal, their manifestations vary by industry. Each sector faces unique challenges and requires tailored solutions.

Healthcare: When Lives Depend on Systems

In healthcare, system failure can be a matter of life and death. Electronic health records (EHRs), medical devices, and hospital networks must operate flawlessly.

A 2020 ransomware attack on Universal Health Services disrupted operations across 400 facilities, forcing staff to revert to paper records and delaying critical care.

- Outdated medical devices with unpatched software

- Poor interoperability between systems

- High pressure leading to procedural shortcuts

The FDA now requires cybersecurity risk assessments for all new medical devices.

Transportation: From Planes to Trains

Transportation systems rely on precise coordination between humans, machines, and infrastructure. A single failure can lead to delays, accidents, or fatalities.

The 2018 crash of Lion Air Flight 610 was caused by a malfunctioning angle-of-attack sensor feeding false data to the MCAS system, which repeatedly forced the plane’s nose down. Pilots struggled to override it.

- Sensor inaccuracies leading to automated errors

- Lack of pilot training on new systems

- Insufficient redundancy in flight control logic

The aviation industry has since improved pilot training and system transparency.

What is system failure?

System failure occurs when a structured network of components—mechanical, digital, or organizational—fails to perform its intended function, leading to disruption, damage, or downtime. It can result from design flaws, human error, environmental factors, or cyber threats.

What are the most common causes of system failure?

The most common causes include design and engineering flaws, software bugs, human error, environmental disasters, and cyberattacks. Often, a combination of these factors leads to cascading failures.

How can system failure be prevented?

Prevention strategies include building redundancy, conducting regular maintenance, implementing fail-safe designs, using AI for predictive analytics, and fostering a strong safety culture. Continuous monitoring and employee training are also critical.

Can AI prevent system failure?

Yes, AI can significantly reduce the risk of system failure by analyzing data to predict issues, automating responses, and enabling self-healing systems. However, AI itself must be carefully designed and monitored to avoid introducing new failure points.

What was the worst system failure in history?

One of the worst system failures was the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, triggered by an earthquake and tsunami. Failures in backup power, cooling systems, and emergency response led to meltdowns and widespread radiation release.

System failure is not an anomaly—it’s an inevitability in complex systems. The key is not to prevent every single failure, but to build systems that can withstand, adapt, and recover. From engineering design to organizational culture, every layer must be fortified. By learning from past disasters, leveraging technology like AI, and prioritizing resilience over convenience, we can create systems that don’t just survive—but thrive—in the face of adversity.

Further Reading: